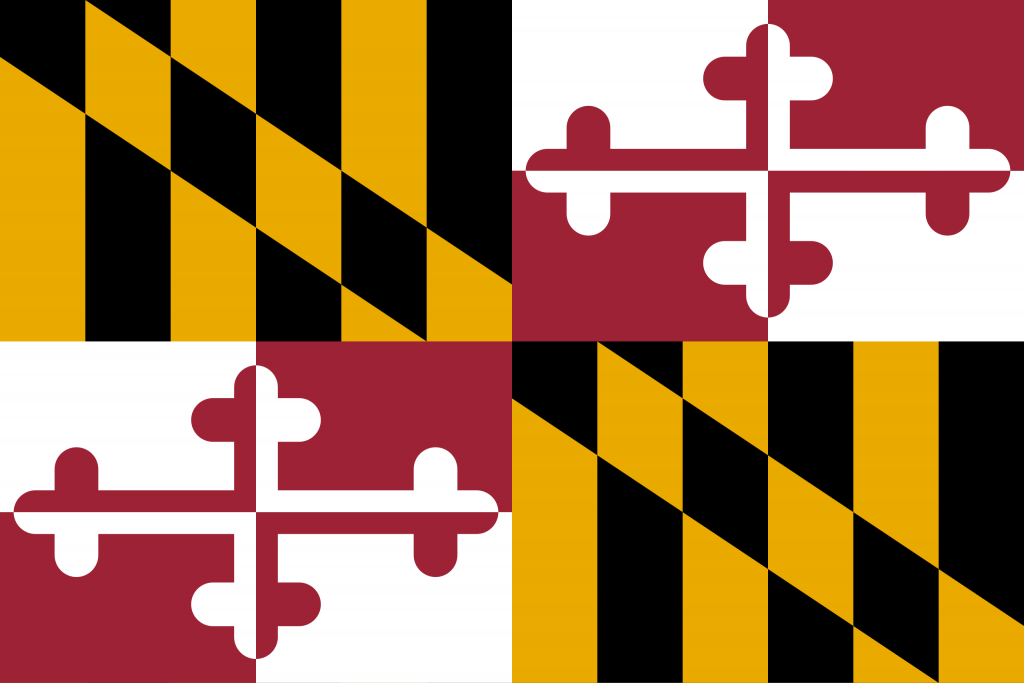

Discover the meaning of the symbols on the Maryland Flag and its iconic design.

Introduction: America’s Most Distinctive State Flag

The Maryland flag stands out among U.S. state flags as one of the most visually striking and historically significant symbols in American heraldry. Unlike the predominantly blue flags of most other states, Maryland’s bold combination of black, gold, red, and white creates an unmistakable visual identity that instantly conveys the state’s unique heritage. This distinctive design features the quartered coats of arms of two founding families—the Calverts and the Crosslands—making it the only U.S. state flag based entirely on British heraldic tradition (alongside Washington, D.C.’s flag). Understanding the meaning of the symbols on the Maryland flag, combined with the Maryland flag history, provides deep insight into the state’s colonial origins, Civil War struggles, and journey toward reconciliation.

The Maryland flag’s design is far more than decorative; it represents centuries of family legacy, colonial ambition, religious tolerance, and ultimately, the healing of a nation divided. Every color, every heraldic element, and every geometric pattern on the flag tells a story that begins in 17th-century England and extends into modern Maryland identity.

Key Takeaways

- The Maryland flag is the only U.S. state flag based exclusively on British heraldic coats of arms, making it unique among all 50 states

- The flag combines the Calvert family’s black and gold “paly” (vertical bars) with the Crossland family’s red and white cross bottony design

- Official adoption occurred on March 9, 1904, though the design appeared informally at public events from 1880 onward

- The flag ranks among the top state flags in North American Vexillological Association rankings (3rd-4th out of 50-72 flags)

- The flag’s adoption symbolized reconciliation between Unionist and Confederate Marylanders following the Civil War

- Maryland law requires the flagstaff ornament to be a gold cross bottony, officially established in 1945

- March 25 marks Maryland Day, commemorating the first colonial landing in 1634

The Distinctive Design of Maryland’s Flag: A Study in Heraldic Precision

A Unique Visual Identity Among State Flags

The Maryland flag’s design stands virtually alone in American vexillology—the scholarly study of flag design and symbolism. While numerous state flags feature symbolic animals, stars, seals, or abstract designs, the Maryland flag is exceptional in being composed entirely of heraldic arms derived from medieval and early modern family crests. This distinctive approach to flag design has earned Maryland’s banner consistent recognition among vexillology experts.

In 2001, the North American Vexillological Association (NAVA) ranked the Maryland flag 3rd-4th best out of all 50 state flags and Washington, D.C., recognizing its superior design quality, historical significance, and visual impact. The flag’s standing in these scholarly rankings reflects both its aesthetic appeal and the meaningful heraldic heritage it represents. Unlike flags that employ generic symbols or state seals, the Maryland flag carries specific genealogical information that connects modern Maryland directly to its colonial proprietors and their family histories.

The flag’s design proved so compelling that it has influenced numerous organizations within Maryland to adopt similar color schemes and symbols. The Baltimore Ravens professional football team incorporated the Maryland flag’s design into their official logo, and the University of Maryland sports teams prominently feature the flag’s colors and heraldic elements in their uniforms—a testament to the flag’s cultural resonance and recognizable distinctiveness.

The Four Quadrants and Their Arrangement: Layout and Heraldic Significance

The Maryland flag’s most striking feature is its systematic arrangement in four equal quadrants, each displaying one element of the combined Calvert and Crossland heraldic arms. This quartered design follows strict heraldic conventions established in medieval European tradition.

Reading from left to right, top to bottom:

- First quarter (top-left): The Calvert family arms—black and gold vertical bars (“paly of six Or and Sable”)

- Second quarter (top-right): The Crossland family arms—red and white with cross bottony

- Third quarter (bottom-left): The Crossland family arms—red and white with cross bottony

- Fourth quarter (bottom-right): The Calvert family arms—black and gold vertical bars

This arrangement creates a perfectly balanced composition: when the flag hangs on a vertical pole or in repose, the Calvert colors occupy the first (upper-left) and fourth (lower-right) diagonal positions, creating a visual frame around the Crossland elements in the second and third quarters. This intentional symmetry is not merely decorative but reflects fundamental heraldic principles of balance and formal arrangement.

Visual Impact and Recognition Factors

The Maryland flag’s impact lies in several design factors that contribute to its exceptional recognizability. First, the color combination—the bright gold contrasting sharply with deep black, alongside vivid red and crisp white—creates a high-contrast design that remains distinct even when viewed from distance or in poor lighting conditions. These are precisely the qualities that vexillologists evaluate when assessing flag design quality.

Second, the geometric precision of the design contributes to its memorability. The vertical bars of the Calvert paly pattern create a rhythm and sense of order, while the cross bottony in the Crossland quadrants provides a distinct heraldic symbol that immediately distinguishes it from other flag designs. This combination of geometric patterns and symbolic elements creates visual complexity without devolving into confusion.

Third, the flag’s bold design reflects the heraldic principle that arms should be readily identifiable and convey information efficiently. In an era when flags served as important military and civic identification markers, a distinctive design conveyed clear messages of authority and heritage. The Maryland flag maintains this practical principle while simultaneously preserving detailed genealogical information.

Historical Origins: The Birth of Maryland’s Flag from Colonial Roots

Understanding Maryland’s Colonial Foundation: George Calvert and the Calvert Dynasty

To fully appreciate the Maryland flag history, one must understand the colonial context from which it emerged. The story begins with George Calvert, 1st Lord Baltimore (1579–1632), an English courtier and politician who served King James I in an elevated administrative capacity—effectively as the king’s secretary of state.

George Calvert came from an established English gentry family with heraldic credentials extending back several centuries. More importantly, he married Alicia Crossland (born c. 1557), a woman of considerable social significance in her own right. Alicia was an heiress to the Crossland family estate, meaning she had no brothers to inherit the family holdings. Under medieval and early modern English heraldic law, female heirs who had no male siblings were permitted—indeed, expected—to display their maiden family coat of arms alongside their husband’s arms. This practice, called “heraldic quartering,” allowed noble and gentry families to merge their heraldic identities through marriage.

George Calvert’s position at court and his marriage into the Crossland family positioned him as a man of influence and ambition. Sometime around 1625, Calvert began petitioning King Charles I for a land grant in the New World. His vision was twofold: to create a profitable colonial venture and, crucially, to establish a refuge for English Catholics, who faced significant persecution in Protestant England. After years of negotiation, King Charles I granted Calvert the title of Baron of Baltimore in 1625—a peerage that itself derived from a Baltimore location in Ireland—and eventually approved his colonial charter.

However, George Calvert died in April 1632, just as the charter process was reaching completion. He never lived to see his colonial vision realized. The honor of establishing and governing the Maryland colony fell to his son, Cecil Calvert, 2nd Lord Baltimore (1605–1675).

Cecil Calvert and the Maryland Charter: The Proprietor’s Vision

Cecil Calvert inherited both his father’s titles and his colonial ambitions. In June 1632, just two months after his father’s death, King Charles I formally granted the Maryland Charter to Cecil Calvert. This charter was extraordinarily generous—it granted Cecil and his heirs “palatinate” rights, meaning they possessed authority nearly equivalent to that of an independent monarch within their colonial domain. The proprietor held the right to collect taxes, establish colonial nobility, wage war, and govern with broad legislative authority.

The Maryland Charter was named in honor of Henrietta Maria of France, the consort of King Charles I, reflecting both the political alliances of the Stuart monarchy and the proprietor’s desire to honor the crown. As proprietor, Cecil Calvert never actually traveled to Maryland but instead governed from his country estate in North Yorkshire, England, while appointing governors and trusted associates to administer colonial affairs.

Cecil Calvert’s most famous administrative action was chartering two ships—the Ark and the Dove—to transport the first colonists to Maryland. In late 1633, the Ark, a 400-ton merchant vessel, departed from Cowes on the Isle of Wight, accompanied by the smaller 40-ton pinnace Dove. The expedition carried approximately 140 English colonists, along with their equipment, supplies, and livestock. Among the passengers was Leonard Calvert, Cecil’s brother, who would serve as the colony’s first governor and the on-site administrator of colonial affairs.

The Ark and Dove sailed southward first, stopping briefly at St. Christopher (now St. Kitts) and at Point Comfort near the mouth of the James River in Virginia, before continuing northward into the Chesapeake Bay. On March 24, 1634, the expedition reached the Potomac River and made its first landing on what is now called St. Clement’s Island (historically Blakistone Island). Here, Governor Leonard Calvert and the colonists erected a cross and celebrated their first Catholic Mass on Maryland soil, marking the establishment of permanent English settlement in the region.

By March 27, 1634, the colonists had selected a permanent settlement site and founded St. Mary’s City on land purchased from the Yaocomico Indians, a branch of the Piscataway Nation. This date—March 25-27, 1634—is commemorated annually as Maryland Day on March 25, celebrating the colonial landing that initiated English settlement in Maryland.

Colonial Use of Heraldic Arms: From Family Crest to Colonial Symbol

In its earliest decades, the Maryland colony did not have an official flag in the modern sense. Instead, the colony used heraldic representations derived from Cecil Calvert’s coat of arms on official documents, seals, and military banners. The coat of arms that Cecil inherited from his father combined both the Calvert paternal arms (the six vertical bars of black and gold) and the Crossland maternal arms (the red and white cross bottony), reflecting Cecil’s hereditary claim to both family lines.

These heraldic arms served practical purposes: they identified colonial authority, marked official documents, and conveyed the proprietor’s legitimacy and pedigree to both colonists and competing colonial powers. The heraldic tradition was not merely symbolic; it conveyed legal and political meaning. The arms demonstrated that Maryland was not an independent venture but rather an extension of legitimate English nobility with the crown’s sanction.

Official Adoption Timeline: From Informal Use to Legal Recognition

While heraldic symbols had been associated with Maryland since the colony’s founding in 1634, the Maryland state flag as we know it today did not receive official recognition until the twentieth century. Instead, the flag’s development followed a fascinating trajectory involving informal popular adoption, Civil War symbolism, and eventual legal formalization.

1634–1776: Colonial Era and Revolutionary Period

During the colonial period and immediately following American independence, Maryland’s government used various flags and symbols, most commonly the state seal on blue or other colored backgrounds. The heraldic arms of the Calvert family were displayed primarily on official documents and seals rather than on flying flags. After the American Revolution, enthusiasm for royalist symbolism naturally waned, and Maryland’s flag traditions entered a period of transition and inconsistency.

1854: Redesigned State Seal and the Reintroduction of Calvert Arms

In 1854, nearly two decades before the modern flag design was officially adopted, Maryland’s legislature redesigned the state seal to prominently feature the Calvert coat of arms. This redesign reintroduced the distinctive heraldic imagery to public consciousness and marked the first major step toward the eventual flag adoption. The seal’s prominence made the heraldic symbols increasingly familiar to Marylanders and positioned the imagery as the state’s official emblematic representation.

1876: First Display at the Centennial Exposition

The first documented public display of a flag incorporating the Calvert and Crossland arms together occurred in 1876, when Maryland displayed such a banner at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. This grand international celebration of American independence and progress provided a high-profile venue for Maryland to present its colonial heritage through the combined heraldic arms. The flag’s appearance at this prestigious event suggested that Marylanders were consciously developing a distinctive state symbol based on their unique heraldic heritage.

1880–1888: Growing Informal Adoption and Civil War Symbolism

Between 1880 and 1888, several significant events accelerated the flag’s adoption. On October 11, 1880, Maryland flew the flag at a parade in Baltimore commemorating the 150th anniversary of the city’s founding (1729–1730). The flag’s appearance at this civic celebration demonstrated growing public support for the heraldic banner as a symbol of Maryland identity.

More significantly, on October 25, 1888, the flag appeared at the Gettysburg Battlefield during ceremonies dedicating monuments to the Maryland regiments of the Army of the Potomac. This particularly symbolic venue—where hundreds of Marylanders had died during a pivotal Civil War battle—gave powerful meaning to a flag that combined the colors used by both Union and Confederate Marylanders during the war. The flag’s appearance at Gettysburg represented a visible statement of postwar reconciliation and reunification.

By 1889, the Fifth Regiment of the Maryland National Guard had officially adopted the combined Calvert-Crossland flag as its regimental color, becoming the first military unit to do so. This military adoption by a state regiment gave the flag official sanction within military and civic institutions, further legitimizing its status as a symbols of state identity.

1904: Legislative Adoption as the Official State Flag

On March 9, 1904, the Maryland General Assembly formally enacted legislation adopting the combined Calvert and Crossland heraldic banner as the official state flag of Maryland. This legislative action transformed what had been an increasingly popular but informal symbol into legal state property. The 1904 adoption reflected more than three decades of growing public enthusiasm for the flag, from its 1876 Centennial Exposition display through its appearances at major civic and military events.

The 1904 act explicitly recognized that the flag design was “steeped in history and symbolism,” as the original blog post correctly noted. Legislators understood they were not creating something new but rather formalizing a symbol that Marylanders had already embraced in their hearts and civic celebrations. The flag’s adoption represented a conscious effort to connect modern Maryland with its colonial heritage and to honor the founding families whose heraldic arms constituted the flag’s design.

1945: Standardization and the Gold Cross Bottony Ornament

After the flag’s official adoption in 1904, the Maryland General Assembly took a further step in 1945 to standardize the flag’s presentation by establishing that the official ornament affixed to the top of any flagstaff displaying the Maryland flag must be a gold cross bottony. This ornament, featuring the trefoil or button-shaped ends characteristic of a bottony cross, became a legal requirement rather than a decorative option.

This 1945 standardization served several purposes. First, it ensured visual consistency across all official Maryland flags, whether displayed by government agencies, military units, or civic organizations. Second, the cross bottony ornament provides a distinctive crowning element that further distinguishes the Maryland flag from all other American flags. Third, the requirement created a specific point of distinction and pride—Marylanders who see a flagstaff topped with a gold cross bottony immediately recognize it as uniquely Maryland.

The Calvert Family Connection: Proprietors and Heraldic Legacy

Lord Baltimore and Maryland’s Founding: The Calvert Dynasty’s Vision

At the heart of the Maryland flag’s design and the state’s entire colonial heritage lies the Calvert family, whose members served as Maryland’s proprietors from the colony’s founding through the eighteenth century. Understanding the Calvert family’s role in Maryland’s founding requires examining not merely their commercial interests but their ideological vision and their position within early modern English political and religious conflicts.

George Calvert (1579–1632): The First Lord Baltimore

George Calvert rose to prominence in the court of King James I through his administrative competence and political acumen. Born in Yorkshire into a gentry family already displaying ambition and intelligence, Calvert educated himself in the law and diplomatic arts, eventually securing a position in the royal court. His career trajectory eventually placed him in roles equivalent to a modern Secretary of State—a position of immense power and influence.

However, George Calvert carried a significant personal commitment that shaped his colonial ambitions: he was a Roman Catholic in an increasingly Protestant England. His faith was not a secret or a private matter; it defined his worldview and his political activities. During a period when Catholics faced systematic legal disabilities in England—prohibitions on holding certain offices, owning property without restriction, and practicing their faith openly—Calvert’s Catholicism was a remarkable fact of his advancement at court.

Calvert’s vision for a colonial venture was not motivated by profit alone (though he certainly hoped for financial returns). He explicitly envisioned Maryland as a refuge for English Catholics fleeing religious persecution. In an era when European powers were engaging in active colonial competition in North America, Calvert saw an opportunity to combine commercial enterprise with religious mission—to establish a profitable colony that would simultaneously provide Catholics with a haven where they could practice their faith without fear of legal persecution.

The Maryland venture represented an innovative approach to religious tolerance that predated the establishment of American religious freedom by more than a century. While many colonies were established on the principle of religious uniformity (Massachusetts Bay for Puritans, Pennsylvania for Quakers), Maryland was founded explicitly on the principle of religious accommodation. Calvert’s ambitions were ultimately realized only after his death, but his vision shaped the entire trajectory of the colony he never saw.

The Calvert Coat of Arms: Symbolism of Achievement and Authority

The Calvert family coat of arms, which occupies the first and fourth quarters of the Maryland flag, carries specific heraldic meaning that reflects the family’s status and achievements. The arms are described in heraldic blazon as “paly of six Or and Sable, a bend counterchanged”—a technical description that translates to the distinctive pattern of six vertical bars alternating between gold (Or, represented as yellow in display) and black (Sable).

The vertical bar pattern, called “paly,” holds specific meaning in heraldic tradition. According to medieval heraldic lore, the pale or vertical stripe represents the vertical pales (stakes or barriers) of fortified palisades. When describing arms with paly design, heraldic tradition holds that these were often awarded to individuals who had demonstrated exceptional military valor—specifically, those who had valiantly defended or stormed a fortification during battle.

According to Calvert family tradition and historical documentation, the Calvert family was granted their distinctive black and gold arms as a reward for exactly this type of military achievement: a distant Calvert ancestor had stormed a massive fortification during battle, displaying the courage and tactical skill necessary to breach defended walls. The heraldic arms thus commemorate not merely a family name but a specific historical achievement, frozen in heraldic symbolism for perpetual remembrance.

The specificity of this heraldic meaning exemplifies one of the great traditions of medieval heraldry: arms were not arbitrary symbols but narratives of family history and achievement. Every element—every color, every symbol, every pattern—conveyed information to those educated in heraldic language. The Calvert paly design immediately conveyed to anyone familiar with heraldry that the family had distinguished itself through military prowess and defensive valor.

This symbolism of strength, fortification, and defensive capability would take on additional resonance during the American Civil War, when Maryland—sitting between North and South, sympathetic to both causes—had to defend its union and its identity against the forces threatening to tear the nation apart.

George Calvert’s Heraldic Legacy: Maternal Inheritance and Family Honor

An equally important aspect of George Calvert’s heraldic legacy is the prominence he gave to his mother’s family, the Crosslands, in his own coat of arms and in the arms that would eventually be quartered on the Maryland flag. This decision was not unusual in heraldic tradition but was nonetheless significant because it gave permanent heraldic recognition to the maternal line.

George Calvert’s mother was Alicia Crossland, an heiress to the Crossland family estates in Yorkshire. Under English common law and heraldic custom, when a woman inherited family property without having brothers to claim the inheritance, she was permitted to display her maiden family’s coat of arms alongside her husband’s arms. This practice ensured that important family lines and property holdings were properly memorialized in heraldic display.

George Calvert honored this tradition by incorporating the Crossland arms into his own heraldic representation, and his son Cecil perpetuated this practice by continuing to quarter the Crossland arms with the Calvert arms. The Maryland flag thus represents not merely the patrilineal descent of the Calvert family but also the matrilineal contribution of the Crosslands—a progressive heraldic approach that acknowledged women’s property rights and family heritage in an era when such acknowledgment was far from universal.

This emphasis on maternal inheritance would ultimately shape the flag’s design in a way that had profound significance during the American Civil War, when Maryland’s population was divided between Union sympathizers (who identified with the Calvert colors) and Confederate sympathizers (who identified with the Crossland colors). The flag’s eventual combination of both family arms came to symbolize the unification of these divided loyalties.

The Crossland Banner: Maryland’s Maternal Heritage and Hidden Civil War Symbolism

The Crossland Family Influence: Heraldic Inheritance and Property Rights

While the Calvert family is rightfully celebrated as Maryland’s colonial proprietors, the Crossland family—represented in the Maryland flag by the red and white quarters and the distinctive cross bottony—holds an equally important place in the flag’s heritage, though often with less public recognition.

The Crossland family was an established gentry family from Yorkshire in northern England, with deep roots in English medieval history. As heraldic heirs, the Crosslands possessed a coat of arms that combined quarters of red (gules) and white (argent), accented with a distinctive cross bottony. The cross bottony—a cross with arms that end in button-like or trefoil shapes—had been employed in English heraldry since medieval times and carried its own historical and symbolic associations.

Critically, when Alicia Crossland married Leonard Calvert (George Calvert’s father), she brought to the marriage not merely her person and dowry but her family’s heraldic status and property rights. Because Alicia had no brothers, she held the position of heraldic heiress—the person responsible for maintaining and perpetuating her family’s heraldic lineage in the next generation. Rather than having her family line eclipsed by marriage, the customs of heraldry ensured that her maiden name and arms were not forgotten but rather prominently displayed in the combined arms of the new generation.

This heraldic accommodation of female inheritance rights meant that George Calvert, though born a Calvert and carrying his father’s name, was simultaneously a representative of the Crossland heritage. His son Cecil inherited this dual heraldic identity, and when Cecil designed his coat of arms—which would eventually become the Maryland flag—he explicitly included both the Calvert and Crossland elements in equal prominence, with each family represented in two quarters of the shield.

The Cross Bottony: Medieval Symbolism in Colonial America

The cross bottony displayed in the Crossland quarters of the Maryland flag deserves particular attention, as this heraldic symbol became freighted with unexpected meaning during the American Civil War. The cross bottony is one of numerous cross variants developed in medieval heraldry to allow different families to distinguish their coats of arms while maintaining adherence to heraldic principles.

In heraldic terminology, the cross bottony (also spelled “botonny”) features arms that terminate in button-like or trefoil-shaped ends, as opposed to pointed or squared endings. The name derives from the French word “bouton,” meaning button. Medieval heraldry incorporated numerous cross variants partly for aesthetic reasons and partly to allow families maximum flexibility in creating distinctive arms. A family might employ a cross fitchy (ending in a point, like a spike), a cross crosslet (terminating in smaller crosses), a cross moline (with curved endings), or a cross bottony (with button or trefoil endings).

The Crossland family’s selection of the cross bottony for their arms reflects both the family’s medieval heraldic heritage and their standing within English gentry. The cross pattern itself carried Christian symbolism—the cross represented the family’s Christian faith and (potentially) any crusading or military historical connections—while the specific form of the bottony cross distinguished the Crosslands from other families using variations of the cross symbol.

This medieval heraldic symbol, established centuries before Maryland was even imagined, would unexpectedly acquire powerful Civil War-era significance when Marylanders from different sides of the conflict began using different elements of the combined Calvert-Crossland arms to express their allegiances.

Civil War Divisions: The Crossland Banner Becomes a Symbol of Confederate Allegiance

The United States Civil War created unprecedented internal division in many states, but perhaps nowhere was this division more acute than in Maryland. As a slave state that bordered the Confederacy and contained significant Confederate sympathies, yet one that remained officially loyal to the Union, Maryland was a house divided against itself. Marylanders who fought in the war found themselves on opposite sides of crucial battles, separated by their political commitments even as they maintained family ties across the conflict lines.

In this context of internal division, the heraldic symbols of the Calvert and Crossland families acquired unexpected symbolic meaning. Unionist Marylanders—those who supported the Union cause—identified with the Calvert colors (black and gold), the colors that the Calvert family had carried forward in Maryland’s colonial tradition. These yellow-and-black colors became known as the “Maryland colors” or “Baltimore colors” and were popularly displayed by Unionist Marylanders.

Confederate Marylanders—those who sympathized with the Southern cause or who actively served in Confederate forces—by contrast adopted the Crossland colors and symbols (red and white cross bottony) as their identifying marker. This shift was not random or arbitrary; it appears to have been a deliberate choice, as documented in historical records. Confederate soldiers from Maryland wore pins and badges featuring the red and white cross bottony, explicitly to identify their home state while distinguishing themselves from other Confederate units.

Historical records indicate that this choice carried particular significance. In Maryland, the Crossland colors came to represent secession sympathies and Confederate allegiance. So powerful was this association that federal authorities stationed in Baltimore during the Civil War actually outlawed the display of red and white colors within the city. Anyone caught displaying the red and white Crossland colors risked arrest and imprisonment, as these colors had become identified with Confederate sympathies and were deemed a threat to Union control of this strategically vital city.

One particularly notable example of this Civil War symbolism involves General Bradley T. Johnson, a Maryland-born Confederate officer. Johnson’s regimental headquarters flag during the Civil War featured a red cross bottony on a white field—a direct reference to the Crossland heraldic arms and Maryland’s heritage, but displayed in service of the Confederate cause. This flag became an identified symbol of Maryland’s Confederate forces and a visible manifestation of how the heraldic symbols had become entangled in the Civil War struggle.

Integration into the State Symbol: Reconciliation Through Combined Arms

The most profound and ultimately most meaningful integration of the Crossland arms into Maryland’s state symbol came not during the Civil War but in the years immediately following it, when Maryland faced the enormous challenge of national reconciliation.

As the Civil War ended and veterans from both sides returned to Maryland to resume their peacetime lives, both the Calvert and Crossland colors retained their strong associations with the conflict they had witnessed. The Unionist (Calvert) colors had been associated with Union loyalty and governmental authority. The Crossland colors had been associated with Confederate sympathies and rebellion. To many Marylanders, particularly those who had fought for one side or the other, these colors might have remained painful reminders of recent conflict and loss.

Yet rather than attempting to suppress one set of symbols in favor of the other, Marylanders pursued a different strategy: they combined the symbols. Unofficial flags incorporating both the Calvert and Crossland arms began appearing at public events in Maryland during the 1880s. These flags, which directly blended the colors and symbols that had represented opposing sides during the war, came to symbolize reconciliation and reunification.

The appearance of these combined-arms flags at major civic ceremonies represented powerful symbolism: the colors that had identified soldiers fighting on opposite sides of the Civil War were now displayed together, suggesting that Marylanders—regardless of which side they had supported—were now ready to work together as citizens of a reunited state and nation.

This symbolism took on particular poignancy on October 25, 1888, when the combined Calvert-Crossland flag was carried by Maryland National Guard troops at the dedication of the Maryland monument at the Gettysburg Battlefield. Gettysburg had been the site of one of the Civil War’s bloodiest battles, where hundreds of Marylanders had died—many of them killed by other Marylanders. By carrying the combined flag—incorporating both the Calvert and Crossland arms—at this solemn ceremony, Marylanders were making a visible statement about their commitment to healing the wounds of war and honoring the sacrifice of all Marylanders, regardless of which cause they had served.

When the Maryland General Assembly officially adopted the combined Calvert-Crossland flag in 1904—nearly forty years after the Civil War’s conclusion—legislators were formalizing what had become clear through decades of popular practice: this flag, combining the symbols of Maryland’s two founding family heritages, was the appropriate symbol for a reunited state. The flag’s adoption represented not merely the selection of a decorative banner but a deliberate political and cultural statement about Maryland’s commitment to reconciliation and unity.

Meaning of the Symbols on the Maryland Flag: Decoding Heraldic Language

The Black and Gold Quarters: Calvert Symbolism and Heraldic Meaning

The black and gold quarters occupying the first (top-left) and fourth (bottom-right) positions of the Maryland flag derive directly from the coat of arms of the Calvert family, Maryland’s colonial proprietors. In heraldic terminology, the pattern is described as “paly of six Or and Sable”—meaning the shield is divided vertically into six alternating stripes of gold (Or, displayed as yellow) and black (Sable).

The vertical stripe pattern, or “paly,” holds multiple layers of meaning in heraldic tradition. Literally, the vertical bars represent the vertical stakes of a palisade or fortification, creating a visual representation of defensive strength and fortification. According to heraldic tradition, paly arms were typically awarded to individuals or families who had demonstrated exceptional military valor in defending or storming fortified positions. The Calvert family tradition holds that their paly arms commemorate a distant ancestor’s valorous storming of a fortification during battle—an act of such military distinction that it was permanently memorialized in the family’s heraldic arms.

In heraldic color symbolism, gold represents nobility, prosperity, wealth, and aristocratic status. Gold’s appearance in heraldry derives from precious metal and royal associations—gold was the most precious metal, displayed in heraldic arms only by noble families of highest rank. The gold in the Calvert arms thus conveyed both the family’s noble status and their associations with wealth and prosperity. When George Calvert established the colony of Maryland, the promise of gold—literal wealth and precious metals—was an important part of the colonial venture’s appeal, even though actual gold discoveries in Maryland proved minimal.

Black, by contrast, represents strength, constancy, endurance, and steadfastness. A shield bearing black conveys the impression of durability and unwavering commitment. The combination of gold and black thus created a heraldic message: the Calverts were noble and prosperous, but also steadfast, constant, and strong. This combination of qualities—aristocratic refinement coupled with military strength and unwavering loyalty—was exactly the image the Calverts wished to project as colonial proprietors.

The Calvert quarters on the Maryland flag thus carry multiple layers of meaning: they represent the colonial proprietorship of the Calvert family, they commemorate the family’s heraldic heritage and military distinction, they suggest the family’s wealth and noble status, and they symbolize the constancy and strength that characterized Calvert rule in Maryland.

The Red and White Quarters: Crossland Symbolism and the Cross Bottony

The red and white quarters occupying the second (top-right) and third (bottom-left) positions of the flag derive from the heraldic arms of the Crossland family, represented in the quarters as a cross bottony. In heraldic description, the Crossland arms are expressed as “quarterly argent and gules, a cross bottony counterchanged”—meaning the shield is divided into quarters of white (argent) and red (gules), with a cross bottony (ending in button or trefoil shapes) that displays red in the white quarters and white in the red quarters.

The cross is the most frequently employed symbol in Western heraldry, reflecting both Christian symbolism and practical historical use (the cross being a common military and civic emblem). However, medieval heraldry developed numerous cross variants to allow families maximum flexibility in creating distinctive arms while maintaining adherence to heraldic principles. The cross bottony, with its distinctive button or trefoil-shaped terminals, represents one of these variants.

The cross bottony’s specific design—with arms terminating in button or bulb-like shapes—is believed to derive from decorative crosses used in medieval ecclesiastical contexts and high-status secular heraldry. The form suggests refinement and aristocratic taste, elevating the cross above the more utilitarian appearance of some other cross variants. The Crossland family’s selection of the cross bottony for their arms reflected their status within English gentry and their participation in the heraldic traditions of the medieval nobility.

Red in heraldic symbolism represents valor, courage, military prowess, and bold action. Red is the color of the warrior and the defender—appropriate for families with military histories or martial ambitions. In the Crossland arms, the red conveys a sense of active courage and martial virtue. White (argent in heraldic terminology) represents purity, innocence, peace, and honor. The combination of red and white—courage and peace—suggests a family committed both to vigorous action and to honorable conduct.

The Crossland arms thus carried a message quite distinct from the Calvert arms: where the Calverts emphasized noble prosperity and steadfast strength through their gold and black paly design, the Crosslands emphasized martial courage coupled with honorable conduct through their red and white cross bottony. When these two heraldic messages were combined in a single flag—as they were formally adopted in 1904—they created a unified heraldic statement: Maryland was founded by families combining noble prosperity and unwavering constancy (Calvert) with martial courage and honorable conduct (Crossland).

Color Significance in Heraldic Tradition: The Symbolic Language of Medieval Arms

Heraldry developed as a complex visual language designed to convey information quickly and efficiently. In an era when literacy was limited, heraldic color and symbol could communicate status, family history, achievements, and even character traits to anyone educated in heraldic conventions. The colors selected for any coat of arms were not arbitrary choices but deliberate communications.

The four colors appearing on the Maryland flag—black, gold, red, and white—each carried specific meanings in medieval and early modern heraldic tradition:

Gold (Or) represents nobility, prosperity, generosity, and preciousness. Gold appeared in heraldry only on the arms of noble families or those granted noble status. The appearance of gold on a shield immediately conveyed that the bearer possessed noble rank or had demonstrated exceptional achievement meriting noble recognition. In the context of the Calvert family, gold represented their status as Lords Baltimore—holders of a peerage in the English nobility. Gold also carried associations with wealth, precious metals, and the prospect of prosperity—meanings particularly significant for a colonial venture meant to generate profit.

Black (Sable) represents strength, constancy, endurance, severity, and wisdom. Black is the color of the night, the color of stone fortifications, the color of steadfast resistance. Where gold represents the promise of prosperity, black represents the strength required to achieve and defend prosperity. The Calverts’ use of black in their arms conveyed that beneath their noble gentility lay strength, determination, and the capacity to defend what they had won.

Red (Gules) represents valor, courage, military prowess, passion, and bold action. Red is the color of blood, of warriors, of soldiers in battle. In medieval heraldry, red appeared prominently on the arms of families with military histories or martial achievements. The red in the Crossland arms conveyed that the family possessed the courage and martial virtue necessary for significant action and defense.

White (Argent) represents purity, innocence, peace, honor, and truth. White is the color of light, of illumination, of moral clarity. In heraldic tradition, white conveyed that a family’s actions were guided by honor and truthfulness. The combination of red and white in the Crossland arms—courage and honor together—suggested a family committed to both vigorous action and moral conduct.

When combined on the Maryland flag, these four colors and their associated meanings created a comprehensive heraldic statement about Maryland’s founding heritage: the state was established by families combining noble prosperity (gold) with steadfast strength (black), martial courage (red), and honorable conduct (white). This combination of qualities—noble, strong, courageous, and honorable—represented the ideal characteristics of leadership in the colonial and early American contexts.

The Mathematical Precision of the Design: Geometric Perfection and Heraldic Rules

The Maryland flag’s design is not merely symbolically significant but also geometrically precise. The four quadrants are exactly equal in size, creating perfect symmetry and balance. This geometric precision is not accidental but rather reflects the fundamental principles of heraldic design.

Medieval and early modern heraldry operated according to strict rules regarding proportion, arrangement, and technical execution. A properly designed coat of arms was not merely an artistic creation but a technical document governed by specific conventions. The quartering of arms—the division of a shield into quarters to display combined family arms—operated according to precise heraldic rules. Each quarter occupied exactly one-quarter of the shield’s area, and the arrangement of quarters followed conventional patterns.

The Maryland flag’s designers adhered rigorously to these heraldic conventions. The four quadrants are mathematically equal. The Calvert arms occupy the first and fourth positions (upper-left and lower-right), creating a diagonal frame around the Crossland arms in the second and third positions (upper-right and lower-left). This arrangement is not arbitrary but reflects the heraldic principle that arms should be displayed with clear visual hierarchy and balanced symmetry.

Furthermore, the proportions and dimensions of the flag itself follow precise geometric relationships. The flag’s aspect ratio—the relationship between its width and height—is carefully calculated to display the heraldic design optimally. When the flag is displayed on a vertical pole or hangs in repose, the quadrants align perfectly, creating a harmonious visual composition.

This geometric precision serves practical purposes: it ensures that the flag is immediately recognizable, that no element is visually dominant over others, and that the heraldic information is clearly conveyed. The mathematical precision of the design reflects the flag’s origins in medieval heraldic tradition, where precision and adherence to convention were paramount.

Civil War Division and Reunification Symbolism: Maryland’s Struggle and Healing

The Border State Crisis: Maryland’s Geographic and Political Position

To fully understand the civil war symbolism embodied in the Maryland flag, one must recognize Maryland’s unique position during the Civil War. Maryland was a border state—a slave state geographically positioned between the Confederacy and the Union, sympathetic to both causes, internally divided in its loyalties, and strategically crucial to both sides of the conflict.

Geographically, Maryland sits at the border between North and South. The Potomac River forms Maryland’s western and southern boundary with West Virginia and Virginia (which seceded to form the Confederacy). Baltimore, Maryland’s largest city, lies less than forty miles north of Washington, D.C., the Union capital. Maryland’s geographic position made it strategically vital: whichever side controlled Maryland controlled access to the Union capital and influenced the entire eastern theater of the war.

Politically and culturally, Maryland was divided. While the state remained officially loyal to the Union—Maryland never seceded from the United States—significant portions of the population sympathized with the Southern cause. Maryland held slaves, and the state’s economy had deep connections to the South. Many Marylanders had family ties to Virginia and other Southern states. When the war began, many Marylanders faced agonizing personal decisions about which side to support.

Militarily, this internal division manifested itself dramatically. Approximately 50,000 Marylanders served in Union forces during the Civil War, but approximately 25,000 Marylanders served in Confederate forces—a remarkable fact that underscores the state’s internal division. Many of these soldiers were Marylanders killing other Marylanders on battlefields across the nation. The Battle of Gettysburg, fought in neighboring Pennsylvania, included regiments of Marylanders on both sides of the conflict. The Antietam Campaign, fought partly in Maryland itself, pitted Maryland against Maryland with devastating consequences.

The personal and family divisions were profound. Families were literally split, with brothers fighting on opposite sides, fathers separated from sons, cousins killing cousins. The political divisions were equally severe, with strong Unionist and strong Confederate factions contending for control of Maryland’s government and resources.

The Civil War Battle for Maryland’s Loyalty: Symbols of Division

Within this context of internal division, the heraldic symbols of Maryland’s founding families acquired new significance. Rather than representing merely historical heritage, these symbols became markers of political allegiance and military identity.

As documented in historical records, Union-sympathizing Marylanders identified with and displayed the Calvert colors—the black and gold that had been formally associated with Maryland’s colonial heritage. These colors became known informally as the “Maryland colors” or “Baltimore colors” and represented Maryland’s loyalty to the Union. Marylanders who supported the Union cause, or who were sympathetic to Union military interests, displayed these colors prominently.

Confederate-sympathizing Marylanders, by contrast, adopted the Crossland colors and symbols—the red and white, and particularly the distinctive cross bottony that had appeared on George Calvert’s heraldic arms and represented the maternal Crossland heritage. This shift was significant and deliberate. By adopting the Crossland symbols, Confederate Marylanders were making a statement: they remained proud Marylanders (the symbols were Maryland’s own heraldic heritage), but they identified with the Confederate cause rather than the Union.

The adoption of Crossland symbolism by Confederate Marylanders was especially visible in military contexts. Confederate soldiers from Maryland wore insignia featuring the cross bottony, particularly on buttons, badges, and pins. These soldiers used the distinctive heraldic symbol to identify their home state while simultaneously distinguishing themselves from soldiers of other Confederate states. The red and white cross bottony became visibly associated with Maryland’s Confederate military forces.

Federal Suppression and the Politics of Symbols: Maryland Under Military Control

The political and military significance of these heraldic symbols reached such intensity that federal authorities took steps to suppress the display of Confederate-associated colors. This was not merely symbolic repression but practical military control: if red and white colors were identified with Confederate sympathies, suppressing their display served the military purpose of preventing open expressions of Confederate support in territory under Union control.

Historical records indicate that federal authorities stationed in Baltimore during the Civil War imposed restrictions on the public display of red and white colors within the city limits. Federal soldiers could arrest and imprison individuals caught displaying these colors, which had become associated with Confederate sympathies and were deemed a security threat to Union control of this strategically vital port city. These restrictions were not merely theoretical: documented cases exist of individuals arrested and imprisoned for displaying red and white colors or other symbols associated with Confederate Maryland.

This suppression reflected the high stakes of controlling Maryland and of controlling symbols of allegiance. As long as red and white Confederate colors could be openly displayed, they served as visible reminders that Confederate sympathies existed within Union territory. By suppressing these symbols, federal authorities attempted to control not merely the display of colors but the political expression and allegiance of Maryland’s population.

Post-War Adoption and Reunification Symbolism: From Conflict to Reconciliation

Following the Civil War’s conclusion in 1865, Maryland faced the enormous challenge that confronted the entire nation: reconciliation and reunification. How could a nation that had torn itself apart, that had experienced brother killing brother and father separating from son, heal itself? This challenge was particularly acute in Maryland, where the internal division had been especially severe and where veterans from both sides had to live together in the same communities and state.

The heraldic symbols that had represented opposing sides during the Civil War were not discarded after the war. Instead, Marylanders pursued a different strategy: they combined the symbols. Beginning in the 1880s, unofficial flags began appearing at public events throughout Maryland. These flags combined the Calvert arms (historically associated with Union loyalty) with the Crossland arms (historically associated with Confederate identity) in a single, unified banner.

This combination of symbols was profound in its meaning. By displaying both the Calvert and Crossland arms together, Marylanders were saying: we acknowledge the heritage that divided us, we remember which sides we supported, but we are now reunited. The colors that had once represented opposing military forces and political allegiances were now displayed together, visibly symbolizing the healing of Maryland’s internal wounds and the reunification of the state’s citizens.

The symbolic significance of this combined flag reached its most poignant expression at the Gettysburg Battlefield on October 25, 1888. On this sacred ground where hundreds of Marylanders had died—many of them killed by other Marylanders—the combined Calvert-Crossland flag was carried by members of the reorganized Maryland National Guard. This flag, combining the symbols that Union and Confederate Marylanders had carried into battle against each other, represented a powerful statement of reunification and healing. By carrying the combined flag at Gettysburg, Marylanders were honoring the sacrifice of all their fellow citizens, regardless of which cause they had served, and expressing commitment to a reunited future.

Official Adoption: The Flag as Reconciliation Symbol

When the Maryland General Assembly officially adopted the combined Calvert-Crossland flag as the state flag on March 9, 1904, legislators were acknowledging what had become apparent through decades of public practice and ceremonial use: this flag, combining the symbols that had represented conflict and division during the Civil War, had become a symbol of reconciliation and reunification.

The 1904 adoption was thus far more than the selection of a decorative banner. It was a deliberate political and cultural statement about Maryland’s commitment to reconciliation, about the state’s determination to move beyond the divisions of the Civil War, and about the power of shared symbols to unite a divided people. The flag represented the triumph of reconciliation over conflict, the healing of wounds, and the commitment to work together as citizens of a united state and nation.

This reconciliation symbolism remains powerful even today. When Marylanders see their state flag—with its distinctive combination of the Calvert and Crossland arms—they are seeing a symbol of their state’s ability to overcome division, to heal historical wounds, and to move forward united. The flag represents not merely state pride but the triumph of unity over conflict and the possibility of reconciliation even after profound division.

Heraldic Elements and Their Traditional Meanings: Understanding Medieval Symbolism

The Bottony Cross Design: Medieval Heraldic Innovation and Evolution

The bottony cross occupying the Crossland quarters of the Maryland flag represents one of heraldry’s most sophisticated innovations: the development of distinctive cross variants that allowed families to create unique arms while maintaining connection to the universal Christian symbolism of the cross itself.

The cross is the most frequently employed symbol in Western heraldry, reflecting both Christian religious symbolism and practical historical usage as a military and civic emblem. However, the universal employment of the cross created a fundamental heraldic problem: if every family using a cross displayed the same simple form, families could not distinguish their arms from one another. Medieval heralds, facing this problem, developed numerous cross variants—subtle variations in the cross’s basic form that allowed families maximum flexibility in creating distinctive arms while maintaining adherence to heraldic principles.

By the medieval period, heraldic tradition recognized dozens of cross variants, each with specific names and characteristics. These included the cross pattée (with flared arms), the cross fitchy (pointed or spiked), the cross fleurie (with fleur-de-lis ends), the cross moline (with curved or split ends), and the cross bottony (with button or trefoil-shaped ends). Each variant carried its own historical associations and was favored by different families and regions.

The cross bottony, also spelled “botonny” and occasionally “botonée,” features arms that terminate in rounded, bulbous, or button-like shapes—hence the name, derived from the French “bouton” (button). The form suggests refinement and aristocratic taste, elevating it above more utilitarian cross variants. The bottony form appears to derive from decorative crosses used in medieval ecclesiastical contexts, suggesting sacred or high-status associations for families employing it.

The Crossland family’s selection of the cross bottony for their coat of arms thus conveyed multiple layers of meaning: connection to Christian tradition and church authority, participation in refined medieval heraldic culture, and aristocratic social standing. When this medieval heraldic symbol was incorporated into the Maryland flag in 1904, it carried all these associations forward into the modern era.

Heraldic Colors and Their Significance: The Language of Medieval Symbolism

The four colors employed on the Maryland flag—black, gold, red, and white—constitute the fundamental language of medieval heraldry. Understanding heraldic color symbolism provides crucial insight into the flag’s meaning and the messages conveyed by its design.

Medieval heraldic tradition recognized that colors conveyed meaning to observers educated in heraldic convention. Rather than arbitrary selections, heraldic colors were deliberate communications of family character, historical achievement, and social status. The primary heraldic colors are:

Gold (Or): Represents nobility, prosperity, generosity, wealth, and precious worth. Gold appears in heraldry only on arms of noble families or those granted special honor. The appearance of gold on a shield immediately conveyed noble rank or exceptional achievement. In the context of the Calvert family arms, gold represented the family’s peerage status as Lords Baltimore and their associations with wealth and prosperity.

Black (Sable): Represents strength, constancy, endurance, seriousness, and unwavering determination. Black is the color of stone fortifications, of night-time watchfulness, of steadfast resistance. Where gold represents promise and prosperity, black represents the strength required to achieve and defend prosperity. The combination of gold and black conveyed that the Calverts possessed both noble prosperity and the strength to maintain it.

Red (Gules): Represents valor, courage, military prowess, bold action, and passionate commitment. Red is the color of warriors, of military achievement, of blood shed in defense of principles. In the Crossland arms, red conveyed martial courage and the willingness to engage in bold action for principles deemed important.

White (Argent): Represents purity, innocence, peace, honor, and moral clarity. White is the color of light, of illumination revealing truth. Combined with red in the Crossland arms, white conveyed that the family’s military courage was guided by honor and moral principle rather than mere aggression.

When these four colors are combined on the Maryland flag—gold and black from the Calvert family, red and white from the Crossland family—they create a comprehensive heraldic statement: Maryland was founded by families combining noble prosperity and steadfast strength (Calvert) with martial courage and honorable conduct (Crossland). This combination of qualities represented the ideal characteristics of colonial leadership and early American governance.

European Heraldic Influences: Maryland’s Connection to Medieval Tradition

The Maryland flag’s design does not emerge from American heraldic innovation but rather represents the direct continuation of medieval and early modern European heraldic tradition into the American colonial context. Understanding Maryland’s heraldic heritage requires recognizing the European—specifically English—roots of the flag’s design and symbolism.

During the medieval and early modern periods, heraldry developed as a sophisticated system of visual communication employed by European nobility, gentry, and emerging merchant classes. Heraldic arms identified families, marked property, conveyed legitimacy and authority, and preserved genealogical information in visual form. The system developed primarily in England and France, spreading throughout Western Europe and subsequently carried to colonial enterprises in North America.

When George Calvert established the Maryland colony, he brought with him not merely his personal ambitions but the full weight of European heraldic tradition. His coat of arms, which combined his paternal Calvert family arms with his maternal Crossland family arms, exemplified medieval heraldic practice—specifically, the practice of quartering arms to display multiple family lineages within a single heraldic shield.

This heraldic quartering reflected complex genealogical and property relationships. The first quarter (top-left) traditionally displayed the family’s primary or paternal arms. Subsequent quarters displayed arms of collateral lines, maternal families, or acquired territories. The arrangement and positioning of these quarters conveyed information to heralds and educated observers about the relative importance of each family line and about the genealogical relationships between them.

The Maryland flag’s design perpetuates this medieval heraldic tradition into the modern era. The flag’s four quarters, arranged according to centuries-old heraldic convention, display the same genealogical and family information that George Calvert’s coat of arms conveyed in the seventeenth century. In this sense, the Maryland flag represents a remarkable continuity: a heraldic design created in seventeenth-century England and adopted as a colonial symbol four centuries ago continues to fly as Maryland’s state flag in the twenty-first century, still conveying the genealogical and heraldic information it was designed to communicate.

Maryland’s Flag in National Context: Unique Among American Symbols

Comparison with Other State Flags: What Makes Maryland Unique

Among the flags of the fifty United States, the Maryland flag stands apart as fundamentally different from the vast majority of its peers. To understand the Maryland flag’s significance, it helps to consider what makes it unique by comparison with other state flags.

The vast majority of American state flags employ a blue field (background) with some central design. Many feature the state seal—an official circular emblem containing images, text, and symbolic elements—placed on this blue background. Others display state symbols: animals (bears, horses, eagles), plants, or abstract designs. A significant number incorporate the state’s initials or name in lettering. Some blend multiple elements together, creating busy or complex designs.

The Maryland flag departs radically from these conventions. Rather than a blue field, it employs all four of its heraldic colors with equal prominence. Rather than a state seal or central emblem, it displays heraldic arms arranged in four equal quadrants. Rather than incorporating state initials or symbols, it displays family coats of arms derived from medieval heraldic tradition. The result is a flag that looks fundamentally different from virtually every other American state flag—a visual distinctiveness that contributes to its recognizability and its high rankings among vexillology experts.

This distinctiveness reflects the flag’s origin in European heraldic tradition rather than in American civic symbolism. While most state flags were designed in the nineteenth or twentieth centuries specifically to serve as state symbols, the Maryland flag is derived from heraldic arms created centuries earlier to serve genealogical and family purposes. The flag thus represents a continuity with European heraldic tradition in a way that other American flags do not.

Unique Features in American Vexillology: Heraldic Innovation and Excellence

American vexillology—the scientific study of flags, their design, symbolism, and use—has emerged as a serious scholarly discipline. The North American Vexillological Association (NAVA), founded in 1967, has established principles for evaluating flag design quality and has conducted systematic surveys and rankings of flags based on design excellence.

According to vexillological principles, an excellent flag design should possess several characteristics:

- Visual distinctiveness: The flag should be immediately recognizable and distinguishable from other flags

- Simplicity: The design should avoid excessive complexity that would be difficult to reproduce or remember

- Meaningful symbolism: The design should convey clear meaning through its symbols and colors

- Historical authenticity: The design should reflect genuine historical or cultural heritage rather than arbitrary choices

- Reproducibility: The design should be capable of being accurately reproduced by various means

The Maryland flag excels according to these vexillological criteria. Its bold color combinations create immediate visual distinctiveness. While its design is detailed, it achieves balance and clarity through geometric precision and adherence to heraldic convention. Its symbolism is deeply meaningful, conveying genealogical information and historical heritage through heraldic imagery. Its design reflects authentic historical tradition rather than contemporary invention. And its design is reproducible: the systematic arrangement of quadrants and heraldic elements allows the flag to be accurately rendered whether displayed on cloth, digitally, or in other media.

These qualities have resulted in consistently high rankings for the Maryland flag in vexillological evaluations. According to NAVA surveys, the Maryland flag ranks among the top state and provincial flags in North America, typically placing 3rd-4th out of 50 state flags and Washington, D.C., in overall design quality. These rankings place the Maryland flag alongside flags such as those of New Mexico (frequently ranked #1) and South Carolina (typically ranking in the top five) as among the finest state flag designs in North America.

Recognition and Rankings by Flag Design Experts

The Maryland flag’s high rankings among vexillological experts reflect several consistent factors that experts identify as contributing to its design excellence.

First, experts consistently praise the flag’s historical authenticity and cultural significance. Unlike flags designed merely to be decorative or to incorporate an official seal, the Maryland flag genuinely represents Maryland’s colonial heritage and genealogical foundations. The flag’s design connects modern Maryland directly to the seventeenth-century figures—George Calvert, Cecil Calvert, and their families—who established the colony. This connection between ancient heritage and modern symbol is rare among state flags and is consistently valued by vexillological experts.

Second, experts appreciate the flag’s adherence to heraldic tradition and technical precision. The flag’s design follows centuries-old heraldic conventions regarding color symbolism, quarter arrangement, and geometric proportion. This technical correctness and respect for traditional principles appeals to scholars and experts who value precision and authenticity in flag design.

Third, experts recognize the flag’s symbolic sophistication and layered meaning. The flag conveys multiple layers of meaning: genealogical information about the colonial founders, heraldic symbolism about family character and achievement, and historical symbolism about Civil War division and post-war reconciliation. This semantic depth—the fact that the flag means different things at different levels of interpretation—is rare among state flags and is highly valued by design experts.

Fourth, experts appreciate the flag’s visual impact and immediate recognizability. The bold color combinations and distinctive quadrant arrangement make the Maryland flag immediately recognizable, even to casual observers unfamiliar with vexillological principles. This combination of visual impact with sophisticated symbolism—accessibility to a general audience combined with depth for informed observers—represents an ideal in flag design.

Cultural Impact and State Pride: The Flag in Modern Maryland Life

The Flag in Maryland’s Civic Identity: From Symbol to Lived Experience

The Maryland flag has transcended its role as a mere legal symbol to become deeply embedded in the cultural identity of Maryland and Marylanders. For citizens of the state, the flag is not merely a geometric arrangement of colors to be flown at government buildings and state occasions; it is an expression of state identity, a marker of belonging, and a source of civic pride.

This cultural embedding of the flag in Maryland identity is visible at multiple levels. At official levels, the flag flies from state buildings, courthouses, schools, and other public institutions. During state holidays and civic occasions, the flag appears prominently in parades, ceremonies, and public gatherings. Government agencies, military units, and civic organizations display the flag as a marker of official status and connection to state authority.

But beyond these official contexts, the flag has become integrated into everyday expressions of Maryland identity and pride. The distinctive colors and symbols appear on clothing, accessories, artwork, and commercial products throughout the state. Marylanders wear Maryland flag apparel not merely as patriotic display but as an expression of identity—a way of announcing to the world “I am from Maryland” and proclaiming pride in that heritage. This informal, everyday adoption of the flag’s symbols by private citizens and businesses demonstrates the flag’s deep cultural resonance.

Incorporation into Sports Teams and Uniforms: The Flag as Expression of Regional Identity

The most visible contemporary expression of the Maryland flag’s cultural significance is its incorporation into the uniforms and logos of Maryland sports teams, particularly professional and university athletic programs.

The Baltimore Ravens, professional football team and one of Maryland’s most prominent sports franchises, incorporate Maryland flag elements directly into their official logo and team identity. The Ravens logo is designed as a stylized shield or badge, with the red and white cross bottony prominently displayed in the lower portion and the black and gold Calvert arms visible in the upper portion. This logo design explicitly references and celebrates Maryland’s heraldic heritage, connecting the professional sports team directly to the state’s colonial history and flag symbolism. Every time Ravens fans wear team apparel or see the team logo on broadcasts and merchandise, they are viewing a direct representation of the Maryland flag’s heraldic elements.

The University of Maryland athletic programs similarly incorporate Maryland flag colors and heraldic symbols into their uniform designs. Maryland football players, in particular, display Maryland flag symbolism prominently on their uniforms. The distinctive combination of colors and the heraldic elements on Maryland uniforms make the team immediately identifiable and create a visual connection between the team and the state’s heritage.

This incorporation of the flag’s design into sports team logos and uniforms serves multiple functions. First, it connects the teams to Maryland identity and heritage, reinforcing the teams’ role as representatives of the state. Second, it makes the flag’s distinctive design visible to millions of people through sports broadcasts, merchandise, and stadium displays. Third, it associates the flag with vitality, competition, and the excitement of athletic competition, reinforcing the flag’s cultural relevance and appeal.

Fashion, Art, and Commercial Applications: Democratizing the Flag’s Symbolism

Beyond sports, the Maryland flag’s distinctive design has become popular in fashion, visual art, and commercial applications throughout Maryland and beyond. The bold colors and geometric precision of the design lend themselves well to artistic interpretation and commercial reproduction.

In fashion, Maryland flag imagery appears on t-shirts, hats, sweatshirts, and other apparel. These garments allow individuals to display Maryland pride and identity in their daily dress. Unlike formal flag display on government buildings, which is governed by regulations and protocol, informal apparel bearing flag imagery is a personal choice to express identity and affiliation.

In visual art, the flag’s striking design has inspired numerous artistic interpretations. Artists incorporate the flag’s colors, geometric patterns, or heraldic imagery into paintings, digital art, sculptures, and other media. Some art works celebrate the flag’s heraldic heritage, rendering the design in historical style to emphasize its medieval connections. Other artists present the flag’s imagery in contemporary or abstract styles, creating new visual interpretations while maintaining connection to the original design. These artistic engagements with the flag demonstrate its cultural significance and its appeal to creative practitioners.

In commercial applications, businesses throughout Maryland incorporate the flag’s design and colors into their branding, marketing materials, and physical environments. Restaurants, retail stores, and service businesses display the flag colors prominently, using the distinctive design to signal local connection and appeal to Maryland customers. Hotels and tourism organizations frequently incorporate the flag’s imagery into their promotional materials, using the distinctive design to market Maryland as a destination. This commercial adoption of the flag’s imagery demonstrates its recognized value as a marker of Maryland identity and its appeal to consumers seeking authentic local connection.

Maryland Day Celebrations and the Flag: Annual Commemoration of Colonial Heritage

On March 25 each year, Maryland celebrates Maryland Day, commemorating the arrival of the first English colonists at what is now St. Clement’s Island on March 25, 1634. This date marks the beginning of English colonial settlement in Maryland and the realization of George Calvert’s vision of a haven for religious tolerance in North America.

Maryland Day celebrations throughout the state prominently feature the Maryland flag. Government buildings display the flag in special honor. Civic organizations, schools, and community groups incorporate the flag into parades, ceremonies, and public gatherings. The flag’s appearance throughout the state on Maryland Day emphasizes the connection between the holiday’s commemoration of colonial heritage and the flag’s representation of that heritage through its heraldic design.

The pairing of Maryland Day and the Maryland flag creates a particularly meaningful cultural conjunction: on the day when Marylanders commemorate their colonial origins and celebrate the arrival of the first colonists, they do so beneath or in the presence of a flag whose very design carries forward the heraldic symbols of those colonial founders. This annual ritual reinforces the connection between the flag and Maryland’s historical identity and ensures that each generation of Marylanders is reminded of the deep historical roots symbolized by their state flag.

Broader Cultural Significance: The Flag as Symbol of Maryland Values

Beyond specific occasions and contexts, the Maryland flag has come to symbolize broader aspects of Maryland identity and values. For many Marylanders, the flag represents the state’s distinctive heritage and its role in early American history. It symbolizes the religious tolerance that George Calvert envisioned and that Maryland has sought to embody, at least in part, throughout its history. The flag’s combination of the Calvert and Crossland arms symbolizes unity in diversity—the ability to honor different traditions and histories while functioning as a unified whole.

The flag’s role in symbolizing Civil War reconciliation and post-war reunification has given it lasting associations with healing, forgiveness, and the possibility of transcending historical divisions. For many Marylanders, particularly those with family histories connecting to the Civil War era, the flag represents the triumph of unity over conflict and the power of reconciliation.

In contemporary contexts, the flag serves as a symbol of Maryland pride and regional identity. It signals belonging to a specific community with distinctive traditions and heritage. It affirms connection to a state with a particular historical narrative and set of values. For many Marylanders, the flag represents not merely government authority or civic obligation but genuine affection for their state and its traditions.

Modern Usage and Regulations: Legal Standards and Proper Display

Official Display Guidelines: Flag Etiquette and Legal Requirements

The proper display of the Maryland flag is governed by specific regulations established in Maryland law and elaborated through official guidelines. These regulations ensure that the flag is displayed respectfully, consistently, and in ways that honor its significance as Maryland’s official state symbol.

According to Maryland regulations, the flag should be displayed under the following conditions:

Display Hours: The Maryland flag should generally be displayed outdoors only during daylight hours, from sunrise to sunset. However, when a patriotic effect is desired, the flag may be displayed 24 hours a day if it is directly illuminated during the hours of darkness. This provision allows for dramatic nighttime displays while maintaining the standard of the flag being well-lit and visible.

Weather Protection: Except as otherwise provided in regulations, the Maryland flag should not be displayed outdoors during inclement weather unless an all-weather flag is used. All-weather flags are constructed from colorfast materials that resist fading and deterioration from exposure to sun, rain, and wind. This regulation ensures that worn, faded, or damaged flags are not displayed, maintaining the flag’s appearance and dignity.

Flagstaff Ornament: If any ornament is affixed to the top of a flagstaff displaying the Maryland flag, that ornament must be a gold cross bottony. This requirement, established in law in 1945, is one of the most distinctive aspects of Maryland flag regulations. The gold cross bottony ornament is not merely decorative; it is a legal requirement that serves to distinguish Maryland flagstaffs from those of other states or organizations. The requirement ensures visual consistency and creates a distinctive identifying marker for Maryland flags. The cross bottony, with its distinctive button-shaped or trefoil-ended arms, immediately signals to observers that the flagstaff displays Maryland’s flag.